Humanity’s quest to understand the natural world is as old as language itself. Long before the advent of the scientific method, our ancestors observed the same earthquakes, eclipses, and geological formations that intrigue us today. Faced with these perplexing phenomena, they crafted stories—rich narratives that wove observation, memory, and metaphor into the fabric of their cultures. For generations, these tales were often dismissed by scholars as mere superstition or poetic fancy. However, an emerging interdisciplinary field known as geomythology is challenging this view, revealing that many ancient legends contain kernels of truth, preserving eyewitness accounts of real events and offering profound insights into how pre-scientific societies interpreted their environment. This research bridges the gap between the humanities and the sciences, suggesting that folklore can be a valuable, if unconventional, historical record, encoding memories of natural disasters and fossil discoveries that span millennia.

Defining Geomythology: Where Folklore Meets Earth Science

Geomythology, a term coined by geologist Dorothy Vitaliano in the late 1960s, investigates the connections between traditional oral narratives and geological or astronomical events. It operates on the premise that many myths, often expressed in supernatural or metaphorical language, originated as attempts to explain dramatic natural occurrences. A volcanic eruption might become a story about an angry god; the discovery of gigantic bones could spawn legends of ancient giants or monsters. The field does not treat these stories as literal scientific reports but rather as cultural artifacts that encode observations and collective memory. By carefully analyzing the details within a myth—descriptions of landscapes, sequences of events, or the behaviors of animals—and cross-referencing them with archaeological, paleontological, and geological data, researchers can sometimes identify the real-world inspiration behind the tale. This process transforms folklore from a subject of purely literary interest into a potential source of information about historical tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, climate shifts, and even encounters with prehistoric fossils.

Unlocking Millennia-Old Memories in Oral Traditions

One of the most compelling assertions of geomythology is that oral traditions can preserve accurate memories of events over astonishingly long periods. Skeptics have questioned whether details could survive thousands of years of retelling, but numerous case studies provide strong evidence. A classic example comes from the Klamath people of the Pacific Northwest, whose legend describes a fierce battle between the sky god Skell and the god of the underworld, Llao, culminating in the collapse of a great mountain and the formation of a deep, blue lake. Geologists recognize this as a remarkably accurate description of the cataclysmic eruption of Mount Mazama roughly 7,700 years ago, which created Oregon’s Crater Lake. Archaeological finds, such as distinctive sandals buried in layers of ash from the eruption, corroborate human presence at the time. Similarly, Aboriginal Australian stories describing coastlines that existed before sea levels rose at the end of the last ice age appear to contain memories stretching back over 10,000 years. These narratives demonstrate that oral traditions are not static; they are living histories, carefully maintained and passed down, capable of preserving the essence of catastrophic events that shaped a people’s world.

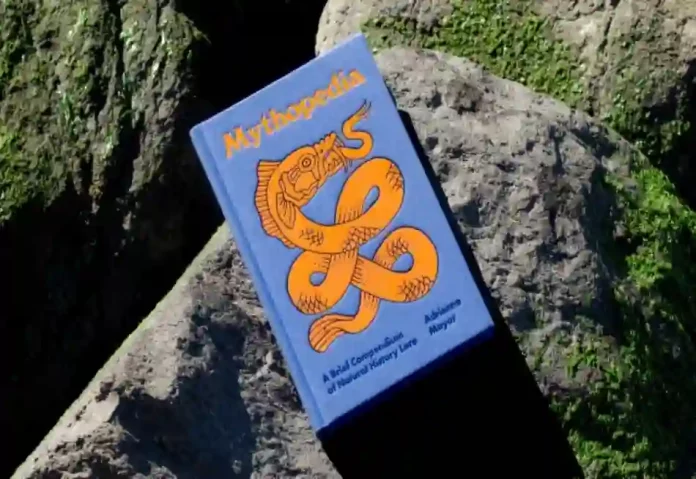

Fossil Legends: Interpreting the Bones of Giants

A particularly vivid branch of geomythology explores how ancient cultures interpreted fossils. Long before paleontology existed as a science, people across the globe unearthed the gigantic, petrified bones of mammoths, mastodons, and dinosaurs. Without a framework of deep time or evolution, they integrated these finds into their existing worldview. Historian and folklorist Adrienne Mayor’s pioneering work has traced how Greek and Roman authors recorded discoveries of “giant” skeletons, often attributing them to fallen heroes from the Trojan War or mythical creatures. By mapping these ancient reports against known fossil beds of Pleistocene megafauna, a clear correlation emerges. Likewise, numerous Native American tribes have traditions about “water monsters” or “thunder birds,” which often correlate to discoveries of dinosaur and pterosaur fossils in their territories. The Lakota story of the *Unktehi*, for instance, a great horned water serpent, is thought to be inspired by the massive skeletons of mosasaurs or similar marine reptiles found in the inland seas that once covered the continent. These fossil legends reveal a universal human impulse to explain tangible, mysterious evidence from the past, transforming bones into actors within a cultural narrative.

The Modern Relevance and Future of Geomythology

Geomythology is more than an academic curiosity; it has practical applications and profound contemporary resonance. For earth scientists, validated geomyths can provide approximate dates for geological events in regions lacking instrumental records, offering clues about seismic history, volcanic periodicity, and past climate patterns. This interdisciplinary dialogue also enriches our understanding of human resilience, showing how cultures processed trauma, memorialized lost landscapes, and built knowledge systems to explain a capricious world. Furthermore, the field encourages us to consider our own era through a geomythological lens. What stories will future cultures tell about the evidence we leave behind? The layers of plastic in strata, the rapid shifts in fossil records, or the radioactive signatures in the ground could inspire new myths about a time of great change and folly. Geomythology ultimately teaches humility and connection. It reminds us that the drive to comprehend our world is a fundamental human trait, linking the first storytellers around a fire to modern scientists in the lab, all seeking to decode the mysteries of the Earth and our place within its long, dynamic history.